With the spring festival of Passover approaching, freedom takes center stage. Yet, in order to celebrate freedom, why do we need to annually recount our experience of enslavement and oppression? Memory is critical to our self-understanding. Our appreciation of freedom was forged through a crucible of persecution and slavery. It is no coincidence that Torah repeatedly warns us, “do not oppress a stranger; for you know the soul of a stranger because you were strangers in the land of Egypt” (Exodus 23:9). Torah is teaching us that the very personal experiences of suffering and slavery shape our orientation to the world. And so it is through the telling and retelling of our story that we free ourselves on seder night. Only by engaging in our narrative can we understand and appreciate the journey to freedom.

What then is the source of Israelite enslavement? While the first chapter of Exodus gives one view of our subtle descent to Egyptian slavery (the rise of “a new king that did not know Joseph” and his persecution of the Israelite minority), the closing chapters of Genesis offer a very different perspective – laying blame squarely at the feet of the Israelites themselves. In my illumination of the Avadim Hayenu portion of the Haggadah, I emphasize this latter reading. The artwork is informed by this midrash:

“Rav Hanina explained, God said to the tribes, ‘You have sold Joseph into slavery. By your lives, every year you will recite, ‘We were slaves to Pharaoh,’ and thereby atone for the sin of selling Joseph.’ And just as Joseph went forth from imprisonment to royalty, so we too have gone forth from slavery to freedom . . .” (Midrash Tehillim, Mizmor 10).

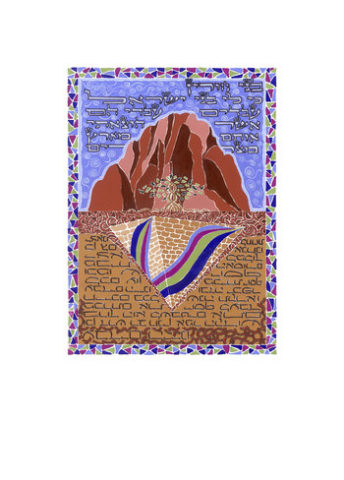

Mount Sinai and a pyramid mirror each other, two halves of a whole. The pyramid is upside down, demonstrating that slavery is an unnatural and inverted state. Mount Sinai is upright, indicating that freedom through Torah is natural – the very purpose for which we were created. The midrash (above) is calligraphed in the background of the pyramid. Note well the shackles of slavery surrounding the pyramid. The serpentine shackles transform into the roots of a tree growing in the foreground of Mount Sinai, a symbol of hope and resilience.

Mount Sinai and a pyramid mirror each other, two halves of a whole. The pyramid is upside down, demonstrating that slavery is an unnatural and inverted state. Mount Sinai is upright, indicating that freedom through Torah is natural – the very purpose for which we were created. The midrash (above) is calligraphed in the background of the pyramid. Note well the shackles of slavery surrounding the pyramid. The serpentine shackles transform into the roots of a tree growing in the foreground of Mount Sinai, a symbol of hope and resilience.

Rav Hanina’s midrash is particularly compelling given the state of intra-Jewish relations in Israel and the Diaspora. Joseph’s fate, a product of brotherly enmity, is based partially on justifiable grievances (Joseph’s haughtiness and their father’s favoritism). However, the brothers’ inability to express their frustration or to restrain their impulses leads to violence instead of healing words. Accordingly, the pyramid is draped with “the technicolor dream-coat.” The colors of the robe carry over into the border, a mosaic of shattered multicolored glass, reflecting the shattered love of a family torn apart by jealousy.

Still, there is always hope for repair. We become redeemed individuals by learning from our misdeeds. Jealousy sparked by parental favoritism, the gift of a robe, and Joseph’s ego ultimately enslave a nation. That is the beginning of our descent to Egypt. Ahavat Yisrael, the absolute love of fellow Jews, is needed now more than ever. Perhaps this is the path to freedom. As Rav Kook said, the repair of sinat hinam, causeless hatred, is ahavat hinam, love motivated by no other reason than Jewish kinship. Differences are real, but they can be negotiated with respect and an understanding that what unites us is greater than that which divides. We are siblings, engaged in building a Jewish nation. By learning from the past, we journey toward a future of freedom.

©Matt Berkowitz and The Lovell Haggadah

Get To Know The Author

Wexner Graduate Fellowship Alum Rabbi Matt Berkowitz (Class 6,) is the Director of Israel Programs for The Jewish Theological Seminary of America and co-founder of Kol Ha-Ot, a Jerusalem-based venture devoted to exploring the arts and Jewish learning. For ten years, Matt served as the JTS Senior Rabbinic Fellow and he is a member of The Wexner Heritage Program Faculty. He completed his undergraduate work in International Relations and Middle East Studies, summa cum laude, at Colgate University. While in Israel, he studied at Pardes and The Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies. He was ordained from JTS in 1999. An accomplished artist, Matt was formally trained in Jewish scribal art in Jerusalem and completed the writing of Megillat Esther, the illumination of several ketubbot, and a limited edition artist portfolio entitled Passover Landscapes: Illuminations on the Exodus, which was acquired by Yale University, exhibited at Yeshiva University Museum (April, 2006) and is on permanent exhibit at The Jewish Theological Seminary. The Lovell Haggadah (jointly published in 2008 by The Schechter Institute and Nirtzah Editions) is based on this work. Rabbi Berkowitz resides in the Arnona neighborhood of Jerusalem. He can be reached online here.