18

Oct 2020

Dissenting Through Listening, Learning and Understanding

WGF/DS Alum Jordanna Amsel (Class 27)

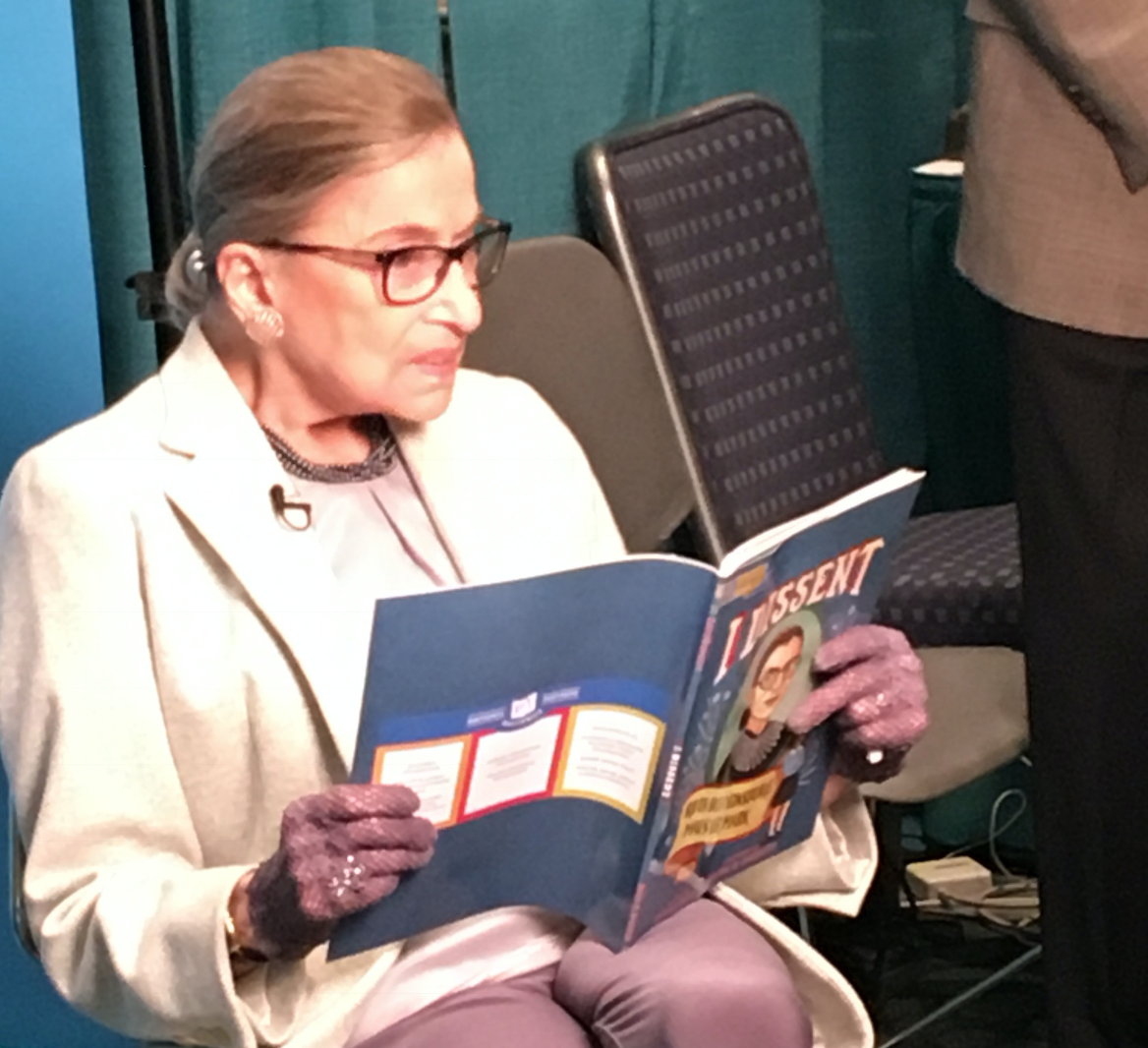

At the 2016 JFNA GA, I had the opportunity to meet Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg z”l as she recorded a message for PJ Library families about the children’s book depicting her life, I Dissent: Ruth Bader Ginsburg Makes Her Mark. I was starstruck by her presence – she was small in stature yet larger than life. I was in awe of her ability to beat the odds as a Jewish woman, to build a family and a career and to do so with grace and humility. Her track record as a dissenter was well known and her moniker as the Notorious RBG showed that she was recognized by a whole new generation as a fighter.

After Justice Ginsburg passed away, I started to learn more about her life. I learned that core to her values was a belief in incremental change. As Dahlia Lithwick shared in one of the recent Identity/Crisis podcast episodes by the Hartman Institute, Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s identity as a “Dissenter” is ironic given that this aspect of her character was mainly a feature of her final decade. Through most of her professional life, Justice Ginsburg’s landmark cases were built on finding judicial pathways to success through understanding the perspectives of the Judges presiding over cases and the issues to which they could relate. As one example, Justice Ginsburg built some of her landmark cases by defending male plaintiffs to persuade the judges to agree that gender inequality should be illegal. She knew that Judges would more easily relate to the stories of these plaintiffs and the injustice they faced. These cases laid the groundwork for future gender inequality cases and ultimately brought about broad-based change for the inequality that women faced.

She was famously close friends with Justice Antonin Scalia and often debated the very issues they disagreed on. In response to questions about how they could be friends, Scalia, a staunch conservative, responded, “I attack ideas, I don’t attack people – and some very good people have some very bad ideas.” Some of Justice Ginsburg’s words about relationships with others expressed a similar sentiment. She quoted her mother-in-law’s advice to “Be a little deaf” and called people to “lead in a way that others will follow.”

In the aftermath of her passing, many people are celebrating the Notorious RBG, the revolutionary, the ‘shock and awe’ dissenter. But I am also interested in celebrating the RBG who was not notorious. The RBG who asked questions, who had empathy and who made incremental change by hearing someone else’s story first. I have been thinking about how that legacy matters in my own life.

I have been living in Israel for 13 months and have had my share of uncomfortable conversations about Black Lives Matter, Zionism, Israeli politics and many other topics. In this election season filled with difficult conversations, I’ll share two that come to mind.

I have been living in Israel for 13 months and have had my share of uncomfortable conversations about Black Lives Matter, Zionism, Israeli politics and many other topics. In this election season filled with difficult conversations, I’ll share two that come to mind.

A few months ago, shortly after George Floyd was murdered, I immersed myself in reading about his killing and to better confront and internalize what it would truly mean to become anti-racist in my own life. The murder and protests that followed became a hot topic at Shabbat meals here in Israel. To my surprise, however, the emphasis was on the looting in NYC and other cities rather than the underlying issue of racism. I was not in Kansas (aka the Upper West Side) anymore!

At first, I found myself pushing back forcefully with declarative statements. I felt I had to embody the opposing viewpoint. Although the people across the table were friends, I started to view them differently for embodying values that I found in contradiction to my own. But with time, instead of digging myself deeper into opposition, I tried to move towards a posture of curiosity and humility. What was it about the current moment that so many found threatening? And how could I help them understand the other viewpoints, the urgent need to focus on fighting racism? I did not have all the answers and preaching was not helpful. I did not fully understand where my friends’ opinions were emerging from and I had to ask more questions. Rather than all my friends being similarly “wrong,” I found that each person I spoke to came to the conversation with different assumptions about the issue at hand.

One friend expressed a deep ambivalence toward the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement because of its position on Israel and questioned our ability to be allies. Others pointed out the uptick in antisemitism in the U.S., which they saw as a result of BLM protests. While most of my friends in the U.S. expressed their discomfort with the movement’s historical rhetoric around BDS, many ultimately decided to align themselves with BLM given the importance of standing against racism. Friends in Israel were generally more distant from the issue of systemic racism in the U.S. and saw the policies associated with BLM as more important and threatening to Israel.

Throughout these conversations, I learned to make measured and difficult choices. When I felt my friends were bringing in new and important points of view, I listened. When I felt I could make a difference, I made sure to speak up. And when I encountered people who I believed espoused views that I didn’t feel should be part of our tolerable discourse, I walked away. Reflecting on these difficult conversations I began to ask myself, at what point is discussion no longer a valid reason to engage with someone who radically departs from one’s values? Or is a moment of radical disagreement exactly when we are called to stay put, engage and listen?

In thinking through this, I remembered an important meeting that occurred way before coronavirus overwhelmed our society. Last fall I had the opportunity to observe a training program (Min HaBe’erot) for Muslim, Jewish and Christian educators and principals. After attending the program, I was offered a ride back to Jerusalem by one of the facilitators, a Palestinian Christian Israeli citizen. I asked him to tell me his story and for two hours I heard the heartbreaking tale of his family who had to flee their home in Lod in 1948. It was painful to hear. While I have read the historical accounts about these stories, I had not heard a first-person account before. There is no counterargument to personal tragedy. I listened to his story and learned about the pain that his family endured. It was empathy for his story that shifted my own thinking on different issues related to the conflict. Since this occurred, I have been thinking about what it means to have a conversation where the opposing side has a portion of truth while still believing my truth with more wholeness.

When listening to the ‘For Heaven’s Sake’ podcast, my colleague, Elana Stein Hain offered new insights on the well-known phrase “Eilu v’Eilu divrei Elokim hayim.” (These – and these – are the words of the living God.) She argues that we do not have to read this as balancing equally appropriate positions. One approach may be better but that does not mean the other approach is completely wrong. The Talmud is conveying a significant value in trying to understand the theory of the other side. There is something valuable about wrapping your head around others’ opinions – about understanding the most serious expression of an opposing argument – even if, in a practical sense, we must choose one position in the end.

To be clear, this is not an argument to let go of our most treasured truths and values. I do wonder, however, if sometimes we become too focused on red lines by dismissing the possibility of this truth differential. As I heard my colleague Donniel Hartman say in the same podcast: “We need our red lines… the question is whether they are at the beginning or the end of the conversation.”

None of this is easy and I am left with more questions than definitive answers. Do we create the space for conversations to occur with people we disagree with or do we cut them off before they happen? Who are we willing to accept as interlocutors? Who can we tolerate in our ‘big tent’ even if we believe they are wrong? I do believe, however, that we have the option of embracing partial truths even if we don’t agree with someone’s complete perspective.

When Dahlia Lithwick described the way Ruth Bader Ginsburg thought about changing minds and ‘bringing people along’ she wrote:

“Let me listen to what you are describing and see if I can make a space for that in my worldview… I think what we are mourning is not just the iconic gangsta rapper version of RBG who set the world on fire, but, for me, a much, much deeper, sadder belief in the art of empathy and persuasion as a means to get us to work together on things for the collective good. I don’t know if that makes sense, but I think that’s always what I think her project was. And I think it’s vanishing before our eyes.”

There is much to glean from Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s legacy. In her memory I am expanding what fits in my categories of pluralism and tolerance and trying to practice the art of bringing others along through empathy, listening, and yes, arguing for the sake of heaven.

Photos were taken by Ruthie Warshenbrot, Director of the Wexner Field Fellowship.

Get To Know The Author

WGF/DS Alum Jordanna Amsel (Class 27) is the Director of Development, Israel programs at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Israel.

Other posts by this author ›