One of our favorite tools in our evaluation and strategic planning toolkit is a Theory of Change (ToC). But sometimes when we suggest a ToC as part of an evaluation, I can see the eyeroll or groan just barely concealed on the faces of our clients. I imagine them thinking:

Theories of Change can feel so cumbersome.

All the boxes and rigid categories can’t possibly account for the emergent nature of our program.

Why are we doing this? We’re still so early in our process—we don’t want to be held accountable for outcomes when we aren’t really sure yet what our outcomes will be!

These are valid concerns. Yet, a recent case of our collaborative work on a ToC affirmed for me how valuable the process of developing a Theory of Change can be—even and especially for new programs.

[This isn’t a blog post explaining a Theory of Change. You can learn about the tool and the merits of the product HERE]

For the past three years, we worked with our partners at the Wexner Foundation with the support of the Jim Joseph Foundation to evaluate the first three classes of the Wexner Field Fellowship as a standalone program. This was a particularly valuable and somewhat unique process. Unpacking the defining elements of our approach to the work will be helpful to others considering undergoing a similar process.

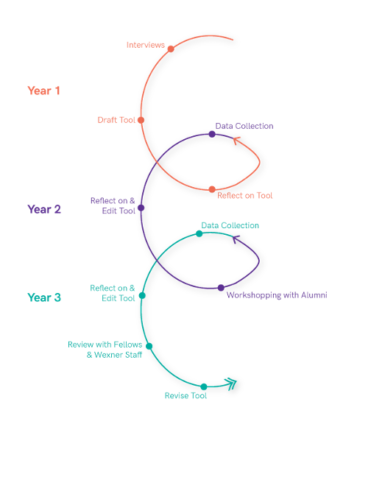

An Iterative, Spiral Process

Rather than work intensely for a few months on a Theory of Change, we developed the ToC throughout the three years of our evaluation, alongside the process of data collection and reporting on program implementation. Here’s how that played out and progressed each year:

Rather than work intensely for a few months on a Theory of Change, we developed the ToC throughout the three years of our evaluation, alongside the process of data collection and reporting on program implementation. Here’s how that played out and progressed each year:

Year 1:

- We began with interviews with key program staff, lay leaders, and funders to articulate the core components of the TOC and to develop a draft narrative and graphic.

- We convened funders and program staff to reflect on the tool together. As we sat around the table, we noted that the design and process felt “Talmudic” in nature. A document was emerging that begged for discussion and reflection.

Year 2:

- After a full year of data collection from Fellows, their supervisors, and Wexner staff, we regrouped for reflection and editing of the first draft. With so many voices reflecting on the core activities and outcomes of the program, we refined the ToC to align with what was happening on the ground.

- With a second draft ready, we began “workshopping” the Theory of Change with select Field Fellowship and Graduate Fellowship Alumni across the country in two different daylong convenings in San Francisco and New York City. These workshops were opportunities for Fellows to engage in discussion about the Foundation’s values and the ToC outcomes to provide a reality check for some of the theorizing that made its way into the document, but that did not match their experiences as Fellows.

Year 3 and Beyond:

- With yet another year of data gathering from the current Field Fellows, and reflections from our workshops in hand, we set out for another stage of reflection and editing to the draft ToC—this time resulting in an even thicker understanding of the kinds of outcomes the program was already manifesting and driving toward for its Fellows.

- We then engaged each of the current three Field Fellows classes in virtual Zoom meetings to reflect on the ToC and its resonance with their experiences.

- We also shared the ToC with a wider circle of Wexner Foundation colleagues to explore how the program’s Theory of Change language resonates with the suite of Wexner Foundation leadership programs.

- Finally, we revised the ToC narrative and graphic one more time to incorporate gleanings from those conversations, as well as findings and discussions that emerged from our final evaluation reporting in late summer 2020. This included a disclaimer regarding how the ToC applies in light of COVID-19. And importantly, Ruthie Warshenbrot, Director of the Wexner Field Fellowship, used the outcomes in the ToC to help prioritize virtual planning during the pandemic.

- We hope, and imagine, that the spiral process of articulating, sharing, and revising will continue as the program continues to evolve.

Benefits of a Longer ToC Development Process Alongside Evaluation

You might wonder if it’s “kosher” to build a Theory of Change while you are running the program. Programs ought to articulate goals and adapt if they aren’t being met, right? Shouldn’t it be all figured out in advance? Well, here are some benefits to taking a more developmental approach to Theory of Change work:

Involvement of stakeholders – Program staff, alumni, program participants, Foundation colleagues, and funders all had time to engage in the ToC development process. Making sure multiple perspectives were heard over time was more manageable than trying to hear from everyone all at once. Gathering waves of feedback as people were ready to offer it and as the program staff was ready to absorb it made the process non-threatening. Engaging Fellows in the process of reflection on the program’s goals contributed to their program experience in that it helped develop greater transparency about the program and what the Foundation hopes participants will “get out of it.”

Bringing the document to life – During hands-on, in-person workshops, participants were able to walk around the room to explore the various outcomes and value statements, using sticky notes and their bodies to place themselves in relationship with the outcomes (“Stand on this side of the room if…”). This exercise was valuable and meaningful because of the depth of the ToC and its resonance with participants—a direct byproduct of the process we undertook. Moreover, small group and whole group discussions animated these theoretical ideas in the ToC document into to real-life issues.

Recognizing that there isn’t ever truly a final product – The very act of engaging stakeholders in reflection on the program’s goals and outcomes is the product itself. Sure, we produce a final version of the narrative and graphic to reflect the program’s thinking at this point in time, but because of the document’s development process, everyone understands that this is more than a static product.

Yes, Theories of Change are helpful because they make clear the outcomes to which programs will be held accountable, and articulating those outcomes clearly can help ease the burden on program staff. But Theories of Change are also valuable because they help organizations focus on these outcomes, even as they are learning and changing components of their program in real time. For stakeholders, ToCs help develop common language and shared frameworks through which to view the program and its effectiveness. Taking the time in a ToC development process to reflect, articulate, share, refine, and rearticulate can help everyone get “on the balcony” (to use a favorite Wexner Foundation adaptive leadership concept from Linsky and Heifetz) to think about what is happening on the “dance floor” of a project, even as they are in the midst of planning and executing.

This blog is also available here.

Photo by Nick Hillier on Unsplash.

Get To Know The Author

WGF/DS Alum Frayda Gonshor Cohen, EdD, (Class 20) is a Senior Project Leader at Rosov Consulting, a mission-driven company that works with funders and grantees to inform and improve Jewish education and engagement.