It is expensive to be Jewish. It is today and it always has been. The cost of being Jewish poses one of the most significant threats to the vibrancy and vitality of our community. As a forward-looking community interested in our future strength, we have an obligation to address the issue of the cost of Jewish life – and particularly the cost of education.

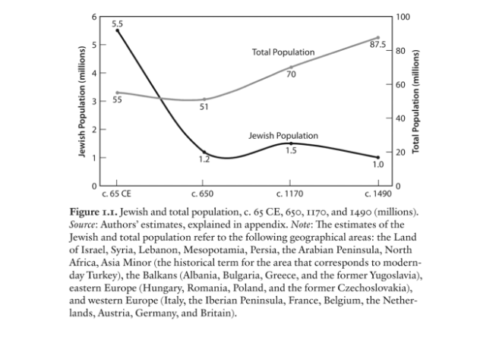

In their book, The Chosen Few: How Education Shaped Jewish History, renowned economists Zvi Eckstein and Maristella Botticin argue that the world-wide Jewish population dropped from 5.5 million in the time of Jesus to 1.2 million in the time of Mohammed not because of persecution, war, famine, or disease, but because of the cost of education.

It was during this time that, in response to the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem and the resulting upheavals of Jewish traditional and life, the rabbis mandated parents give their sons a Jewish education. The institution of an educational norm designed to create a literate religion – a community in which each individual could carry on our heritage and traditions even after the destruction of the temple and the cessation of the thrice annual pilgrimage to Jerusalem – was a noble drive towards continuity in the context of deep discontinuity.

It was during this time that, in response to the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem and the resulting upheavals of Jewish traditional and life, the rabbis mandated parents give their sons a Jewish education. The institution of an educational norm designed to create a literate religion – a community in which each individual could carry on our heritage and traditions even after the destruction of the temple and the cessation of the thrice annual pilgrimage to Jerusalem – was a noble drive towards continuity in the context of deep discontinuity.

But for the average Jew, the overwhelming majority of whom were subsistence farmers, the costs of the new education requirements were substantial: paying for a teacher, supplies, and losing sons who would otherwise be working the fields. For too many, the cost was untenable. As a result, Eckestein and Botticin argue, Judaism became a religion of the wealthy who could afford an education for their children and for the deeply devoted who would sacrifice nearly anything to remain within communal norms. For the remainder of Jews, those for whom the significant cost of Judaism’s mandate to educate wasn’t tenable, the path of least resistance was to choose another sect with whom to associate. As a result, the Jewish population dropped dramatically.

Zoom forward two thousand years and we are, again, seeing the same story repeat itself: the cost of Jewish life is become a dividing line between those who can participate and those who can’t.

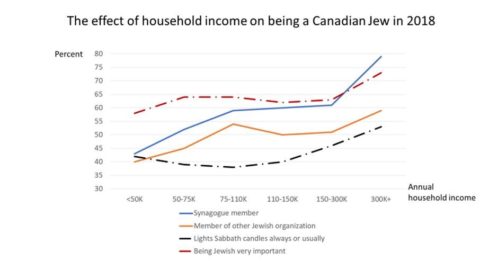

Here in Canada, our most recent study of the Jewish community clearly demonstrates the impact of household finances on Jewish life. More affluent members of our community are more likely to engage Jewishly than the less affluent. What’s particularly notable is that this trend holds true both on items where a financial transaction is part of the equation (synagogue membership, being a member of another Jewish organization) and in areas of engagement where there is no direct financial transaction (lighting Shabbat candles and the importance of being Jewish). For the membership items, it is understandable that pricing matters. What is notable is that for the other items, the sociology of belonging plays a role. If I’m not able to afford to be part of the community – a member of a synagogue or JCCs, send my kids to Jewish camp or school, live in a Jewish neighborhood or shop in a kosher store – I’ll be less likely to see Judaism as important in my life and to light Shabbat candles.

It’s expensive to be Jewish: Jewish education and Jewish food, Jewish neighborhoods and Jewish experiences are all expensive. But we cannot afford for the cost of Jewish living to drive people away from our community.

It’s expensive to be Jewish: Jewish education and Jewish food, Jewish neighborhoods and Jewish experiences are all expensive. But we cannot afford for the cost of Jewish living to drive people away from our community.

So where to from here?

Recent experiments have demonstrated that we can make a difference. Here in Toronto, new programs in our day schools and camps to change the culture of pricing have resulted in dramatic increases in participation. We’ve demonstrated that with the right strategies – powered by significant philanthropy – we can turn the ship in the right direction.

As one example, five years ago our Jewish community high school, TanenbaumCHAT, had 175 students enrolled in Grade 9. Through an evidence-based approach, we launched the TanenbaumCHAT Affordability Initiative to retain a greater number of day school students from middle school to high school and attract new students from public and independent schools into Jewish high school. The initiative combined lowering the cost to educate with significant new, and easily accessible scholarships. In September, we expect a Grade 9 class of 370 students. We can make a difference.

Beyond the technical details of how to get there, there are three key culture shifts that must take place (those demonstrated below used educational examples), but the same could hold true for synagogues, JCCs, camps, and other experiences.

- A Pricing Model

We need a systemic pricing model using three numbers: The cost to educate, tuition, and individualized price. The cost to educate is all educational expenses divided by the number of students. Tuition should be set at the cost to educate – full paying families therefore pay the costs associated with their child. For those who can’t afford full tuition, an easily accessible and transparent scholarship program should be available to tailor the price to their household income (and assets).

- Addressing the unique psychology of asking for help

It is not easy to ask for help. This is especially true for those who, in the rest of their lives, are givers but because of the cost of Jewish living need to put out their hand and ask for help. Simplified processes, transparency, anonymity, and a long line of sight are amongst the design principles necessary to make the process of accessing scholarships dignified and accessible.

- Creating a culture of belonging, not a transaction of membership

As the Canadian data demonstrates, confronting affordability as a barrier for Jewish engagement is not only about scholarships, but also about changing culture. We cannot afford for Judaism to be a transaction-based religion where community members associate only through a fee for service model. Instead, we need to create a culture of belonging which make price a minor piece of the equation.

We live in a world where being Jewish is a choice. As a community, we need to ensure that the choice to disconnect is not a decision based on economics.

Photo by Ivan Aleksic on Unsplash

Get To Know The Author

WGF/DS Alum Daniel Held (Class 22) is the Executive Director of UJA Federation of Greater Toronto’s Koschitzky Centre for Jewish Education.