17

Aug 2020

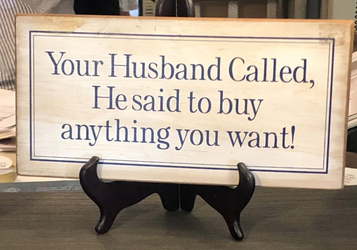

Your Husband Called, He Said to Buy Anything You Want!

WHP Alum Hava Leipzig Holzhauer (Boca Raton 07)

When I received news of The Wexner Foundation’s intent to launch a summit on gender equity and safety with a focus on the Jewish workplace, I was all in.

In my third year of law school, I was absorbed by assessing the competency of the idea of ‘separate but equal’ as applied to modern situations. (Modern was 1998.) For a final brief, I chose to research the roles of men and women in Orthodox Judaism, finding supporting arguments both in and out of favor with the conclusion that separate roles and obligations can indeed lead to gender equality.

Exploring the concept of ‘separate but equal’ put me in wonder of whether true gender equality could even exist. If men and women identify, are by nature or are commanded differently than one another – in aspirations, in household roles, in behaviors, in characteristics, in job selections, in interests, in required religious and ritual observance – can and do we truly attribute to each the same value? I determined that theoretically we could, but in how things played out in reality – not even close.

In my early work as a lawyer, I focused on employment. I worked on discrimination cases that included gender, fair pay, pregnancy and the relatively new Family Medical Leave Act (which in a nutshell, among other things, said you can’t fire women for having babies). In this early part of my career, I took on what might be considered the ‘big things’ when it came to striving for gender equity and safety. For me, attaining gender equity meant taking advantage of legal tools available to create fairness for women and to level the playing field.

The law mirrors societal attitudes. When it comes to valuing ‘male’ over ‘female’, we have a long history of inequality. For one, ‘we the people’ was not originally understood by most to include women. And then there’s coverture – a legal doctrine holding that women had no legal identity. At birth, females were subsumed by their fathers and at marriage by their husbands. Although the 14th Amendment called for ‘equal protection of the laws’, it was not legally determined to include women until 1971. Even the writers of the 15th Amendment (intent to prevent states from denying the right to vote based on ‘race, color or previous condition of servitude,’) had no intention to include women under its protections. Also, until 1971, only women could be legally refused a job if they had pre-school-aged children. And it was not until 1993 that all 50 states finally considered marital rape a crime. Although today’s legal protections seeking to promote women’s equality – and equality across the gender spectrum – come from a much more modern understanding of equality principles, this is just a tiny window into the history against which we are still pushing.

The law, I soon learned, was only one strategy for improving equality and equity for women in the workplace. When I shifted from lawyering into Jewish non-profit management in 2013, I began noticing ‘little things’ happening to thwart progress in the fight.

These ‘little things’ really weren’t little at all. They were incidents making me uncomfortable in our community. They were unhealthy interactions in our board rooms, by-standing and lack of intention in our hiring conversations, the absence of women leading in our largest houses of worship and in our top Jewish organization positions, and micro-aggressions from male donors to female staff, among many others.

Like many of us, today I continue to witness our Jewish community favoring men in myriad contexts. These stories are important to tell. I once spoke to a headhunter about a Federation CEO position before putting in the effort to apply. He let me know that the board favored a male hire. I thanked him for being direct. I more than once sat in a donor meeting where unsolicited advice was given about my wearing pants instead of skirts – about my wardrobe being too lawyer-like and colorless – and even about the improper long length of my hair, (‘You’re not Jennifer Anniston’, said the donor).

Once a supervisor asked me to get up from my seat and then he moved himself to my seat just before a prospect walked into the room to hear our pitch. When I asked why, he explained – as he moved closer to what was soon to be the seat occupied by that prospect – that our pitch would be more powerful this way. I have co-interviewed job applicants with colleagues who question how women with young children will be able to handle the job. I have seen male colleagues go over the heads of women their equals in job hierarchy to work with a man instead. I have also seen countless all-male panels of Jewish scholars and Jewish clergy along with the occasional male panels where a female educator is brought in to improve the optics. There are so many ‘little things’ we have all seen and heard.

When I viewed gender equity through the lens of the law only, I focused on making changes to the way we do things. In looking through other lenses, I saw that widespread, systemic changes are needed – not just in what we do, but in how we think.

Changing how we think of women and about women at work requires paying persistent attention to the day-to-day interactions, comments and choices made by and around us. It is imperative to intervene when ‘small things’ happen that exacerbate gender inequality. In the Jewish institution and organizational world, there is no hiding the disparity that exists. Our organizations have men at the helm 70% of the time; our largest organizations have men at the helm around 90% of the time. We pay our male executives more. As a Jewish work community, we both present on paper and experience anecdotally, as valuing men over women.

Just before the pandemic hit, someone shared with me about a Jewish organization’s committee meeting that went like this: About 20 committee members, including the chair and two staff persons, sat around a boardroom table. The guest speaker – a woman – was set to address the committee via video. When her image appeared on the screen, there was mumbling in the room as one committee member asked if anyone wanted to let her (the guest speaker) know she needed a haircut.

This example is one of many which gets at the heart of our attitudes about women. No one spoke up in that boardroom. Some committee members complained amongst themselves. No one – not even a staff member – said anything out loud – or followed up to let the committee know without mincing words that commenting on someone’s physical appearance in this manner is crude, rude, unacceptable and not in alignment with our Jewish values or the value we attribute to women.

To change how we think as individuals and as a community about women in the workplace, we need to pay closer attention and to target changing thinking right along with changing action. We will continue to perpetuate disparity if we allow, for example, our executives and institutions to sign onto aspirational pledges about workplace equity without also having a mechanism in place to hold the signatories accountable.

While vacationing in North Carolina this summer, I walked into one of my favorite shops to find this sign: Your Husband Called, He Said to Buy Anything You Want! There was a time some could laugh at this. Some I’m sure still find it amusing today. But I just can’t. If we continue to laugh and ignore, if we continue to make it okay to place value in the characteristics, behaviors and historic traditional roles of men’s dominance over women, we will not change hearts and minds, which is what we need to do to overcome the systemic challenges to women’s equality.

We will continue to make strides toward gender equity and safety only by choosing to intervene, by proactively planning our workplace practices and policies and by addressing day-to-day the one-sidedness that we witness.

Get To Know The Author

WHP Alum Hava Leipzig Holzhauer, J.D., (Boca Raton 07) is owner and principal consultant at Transformative Communications and Management (TCom), lecturer of Civil Rights Law and Executive Director of the Konar Center for Tolerance and Jewish Studies at Nazareth College in Pittsford, New York.

Other posts by this author ›